Abstract

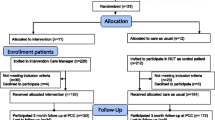

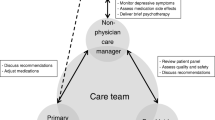

OBJECTIVE: To compare collaborative care for treatment of depression in primary care with consult-liaison (CL) care. In collaborative care, a mental health team provided a treatment plan to the primary care provider, telephoned patients to support adherence to the plan, reviewed treatment results, and suggested modifications to the provider. In CL care, study clinicians informed the primary care provider of the diagnosis and facilitated referrals to psychiatry residents practicing in the primary care clinic.

DESIGN: Patients were randomly assigned to treatment model by clinic firm.

SETTING: VA primary care clinic.

PARTICIPANTS: One hundred sixty-eight collaborative care and 186 CL patients who met criteria for major depression and/or dysthymia.

MEASUREMENTS: Hopkins Symptom Checklist (SCL-20), Short Form (SF)-36, Sheehan Disability Scale.

MAIN RESULTS: Collaborative care produced greater improvement than CL in depressive symptomatology from baseline to 3 months (SCL-20 change scores), but at 9 months there was no significant difference. The intervention increased the proportion of patients receiving prescriptions and cognitive behavioral therapy. Collaborative care produced significantly greater improvement on the Sheehan at 3 months. A greater proportion of collaborative care patients exhibited an improvement in SF-36 Mental Component Score of 5 points or more from baseline to 9 months.

CONCLUSIONS: Collaborative care resulted in more rapid improvement in depression symptomatology, and a more rapid and sustained improvement in mental health status compared to the more standard model. Mounting evidence indicates that collaboration between primary care providers and mental health specialists can improve depression treatment and supports the necessary changes in clinic structure and incentives.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Kazis LE, Ren XS, Lee A, et al. Health status in VA patients: results from the Veterans Health Study. Am J Med Qual. 1999;14:28–38.

Hays RD, Wells KB, Sherbourne CD, Rogers W, Spritzer K. Functioning and well-being outcomes of patients with depression compared with chronic general medical illnesses. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52:11–9.

Ormel J, VonKorff M, Ustun TB, Pini S, Korten A, Oldehinkel T. Common mental disorders and disability across cultures. Results from the WHO Collaborative Study on Psychological Problems in General Health Care. JAMA. 1994;272:1741–48.

Wells KB, Golding JM, Burnam MA. Chronic medical conditions in a sample of the general population with anxiety, affective, and substance use disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 1989;146:1440–6.

Katon W. The epidemiology of depression in medical care. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1987;17:93–110.

Narrow WE, Regier DA, Rae DS, Manderscheid RW, Locke BZ. Use of services by persons with mental and addictive disorders. Findings from the National Institute of Mental Health Epidemiologic Catchment Area Program. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50:95–107.

Coyne JC, Schwenk TL, Fechner BS. Nondetection of depression by primary care physicians reconsidered. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1995;17:3–12.

Lyness JM, Cox C, Curry J, Conwell Y, King DA, Caine ED. Older age and the underreporting of depressive symptoms. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1995;43:216–21.

Magruder HK, Zung WW, Feussner JR, Alling W, Saunders WB, Stevens HA. Management of general medical patients with symptoms of depression. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1989;11:201–6.

Simon GE, VonKorff M, Wagner EH, Barlow W. Patterns of antidepressant use in community practice. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1993;15:399–408.

Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Gibbon M, First MB. The structured clinical interview for DSM-III-R (SCID): history, rationale, and description. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:624–29.

Schulberg HC, Katon W, Simon GE, Rush AJ. Treating major depression in primary care practice: an update of the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research Practice Guidelines. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:1121–27.

Goldberg HI, Wagner EH, Fihn SD, et al. A randomized controlled trial of CQI teams and academic detailing: can they alter compliance with guidelines? Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 1998;24:130–42.

Horowitz CR, Goldberg HI, Martin DP, et al. Conducting a randomized controlled trial of CQI and academic detailing to implement clinical guidelines. Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 1996;22:734–50.

Wagner EH, Austin BT, Von Korff M. Improving outcomes in chronic illness. Manag Care Q. 1996;4:12–25.

Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, et al. Population-based care of depression: effective disease management strategies to decrease prevalence. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1997;19:169–78.

Von Korff M, Gruman J, Schaefer J, Curry SJ, Wagner EH. Collaborative management of chronic illness. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:1097–102.

Hunkeler EM, Meresman JF, Hargreaves WA, et al. Efficacy of nurse telehealth care and peer support in augmenting treatment of depression in primary care. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:700–8.

Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, et al. Collaborative management to achieve treatment guidelines. Impact on depression in primary care. JAMA. 1995;273:1026–31.

Katon W, Robinson P, Von Korff M, et al. A multifaceted intervention to improve treatment of depression in primary care. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53:924–32.

Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, et al. Stepped collaborative care for primary care patients with persistent symptoms of depression: a randomized trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:1109–15.

Wells KB, Sherbourne C, Schoenbaum M, et al. Impact of disseminating quality improvement programs for depression in managed primary care: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2000;283:212–20.

Randall M, Kilpatrick KE, Pendergast JF, Jones KR, Vogel WB. Differences in patient characteristics between Veterans Administration and community hospitals. Implications for VA planning. Med Care. 1987;25:1099–104.

Wolinsky FD, Coe RM, Mosely RR, Homan SM. Veterans’ and nonveterans’ use of health services. A comparative analysis. Med Care. 1985;23:1358–71.

Cebul RD. Randomized, controlled trials using the metro firm system. Med Care. 1991;29:JS9-JS18.

Williams JW Jr, Barrett J, Oxman T, et al. Treatment of dysthymia and minor depression in primary care: a randomized controlled trial in older adults. JAMA. 2000;284:1519–26.

McDonell M, Anderson S, Fihn S. In: The Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project: A Multi-Site Information System for Monitoring Health Outcomes. Presented at the Annual Meeting of the Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Service, Washington DC, February 12–14, 1998. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs; 1998.

Samet JH, Rollnick S, Barnes H, Beyond CAGE. A brief clinical approach after detection of substance abuse. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:2287–93.

Simon GE, Revicki D, VonKorff M. Telephone assessment of depression severity. J Psychiatr Res. 1993;27:247–52.

Department of Veterans Affairs. Major Depressive Disorder Clinical Guidelines. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs; 1997.

Chilvers C, Dewey M, Fielding K, et al. Antidepressant drugs and generic counseling for treatment of major depression in primary care: randomized trial with patient preference arms. BMJ. 2001;322:772–75.

Depression Guideline Panel. Depression in Primary Care: Clinical Practice Guideline. Publication Nos. AHCPR 93-0550 and 93-0551. Rockville, Md: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, US Department of Health and Human Services; 1993.

Brody DS, Khaliq AA, Thompson TL. Patients’ perspectives on the management of emotional distress in primary care settings. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12:403–6.

Padesky CA, Greenberger D. Clinician’s Guide to Mind Over Mood. New York: The Guilford Press; 1995.

Greenberger D, Padesky CA. Mind Over Mood. New York: The Guilford Press; 1995.

Depression. (Recurrent and Chronic) [videotape]. New York: Time-Life Medical Patient Educational Media; 1996.

Derogatis LR, Lipman RS, Rickels R, Uhlenhuth EH, Covi L. The Hopkins Symptom Checklist, a measure of primary symptom dimensions. In: Pichot P. ed. Psychological Measurements in Psychopharmacology: Problems in Pharmacopsychiatry. 7th ed. Basil, Switzerland: Kargerman; 1974: 79–110.

Kazis LE. The Veterans SF-36 Health Status Questionnaire: Developments and Application in the Veterans Health Administration. Medical Outcomes Trust Monitor. 2000;5:1–14.

Lin EH, VonKorff M, Russo J, et al. Can depression treatment in primary care reduce disability?: A stepped care approach. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:1052–58.

Simon GE, Lin EH, Katon W, et al. Outcomes of “inadequate” antidepressant treatment. J Gen Intern Med. 1995;10:663–70.

Saunders K, Simon G, Grothaus L. Assessing the feasibility of using computerized pharmacy refill data to monitor antidepressant treatment on a population basis: a comparison of automated and self-report data. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51:883–90.

Malone DC, Billups SJ, Valuck RJ, Carter BL. Development of a chronic disease indicator score using a Veterans Affairs Medical Center medication database. IMPROVE Investigators. J Clin Epidemiol. 1999;52:551–57.

VonKorff M, Wagner EH, Saunders K. A chronic disease score from automated pharmacy data. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:197–203.

Liang KY, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 2001;73:13–22.

Coulehan JL, Schulberg HC, Block MR, Madonia MJ, Rodriguez E. Treating depressed primary care patients improves their physical, mental, and social functioning. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:1113–20.

Glasgow RE, Hiss RG, Anderson RM, et al. Report of the health care delivery work group: behavioral research related to the establishment of a chronic disease model for diabetes care. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:124–30.

Wagner EH, Glasgow RE, Davis C, et al. Quality improvement in chronic illness care: a collaborative approach. Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 2001;27:63–80.

Nierenberg AA, Wright EC. Evolution of remission as the new standard in the treatment of depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(suppl 22):7–11.

Simon GE, VonKorff M, Rutter C, Wagner E. Randomised trial of monitoring, feedback, and management of care by telephone to improve treatment of depression in primary care. BMJ. 2000;320:550–4.

Chaney EF, Rubenstein LV, Hedrick SC, Yano EM. Approaches to Guidelines Implementation: Primary Care Depression Treatment. Presented at HSRD Service 18th Annual Meeting, Washington, DC, March 20–24, 2000. Washington DC: Department of Veterans Affairs; 2000.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This report presents the findings and conclusions of the authors. It does not necessarily represent those of the VA or HSR&D Service.

The Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Health Services Research and Development Service supported this research.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hedrick, S.C., Chaney, E.F., Felker, B. et al. Effectiveness of collaborative care depression treatment in veterans’ affairs primary care. J GEN INTERN MED 18, 9–16 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.11109.x

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.11109.x